Rancho La Cienega O' Paso de la Tijera, is the lengthy name given to a series of adjoining adobe structures located on the eastern side of the Baldwin Hills. The history of these early adobes is obscure. It is uncertain when they were constructed and by whom. At 3725 Don Felipe Drive, the structures are situated within the city limits of Los Angeles and possibly may be the oldest surviving building in the city. They may have been built between 1790 and 1795. The Avila adobe on Olvera Street in the downtown area was known to be built in 1818, almost thirty years after the adobes on Don Felipe Drive, but it retains the honor of the oldest residence in Los Angeles.

Rancho La Cienega O' Paso de la Tijera, is the lengthy name given to a series of adjoining adobe structures located on the eastern side of the Baldwin Hills. The history of these early adobes is obscure. It is uncertain when they were constructed and by whom. At 3725 Don Felipe Drive, the structures are situated within the city limits of Los Angeles and possibly may be the oldest surviving building in the city. They may have been built between 1790 and 1795. The Avila adobe on Olvera Street in the downtown area was known to be built in 1818, almost thirty years after the adobes on Don Felipe Drive, but it retains the honor of the oldest residence in Los Angeles.In 1843, Manuel Micheltorena, the Mexican Governor of Alta California, granted Rancho La Cienega O' Paso de la Tijera to Vicente Sanchez of Los Angeles. The long title of Rancho La Cienega O' Paso de la Tijera is actually two names combined. "La Cienega" is derived from the Spanish word - Cienaga, which means swamp or marshland. The name refers to the marshes in the area between Baldwin Hills and Beverly Hills. The cienegas were created from overflow from the Los Angeles River, which until the winter of 1824-25 emptied into Santa Monica Bay via La Ballona Creek. Springs trickling down canyons from Baldwin Hills continued to feed water to the swamps after the river changed to its present course. The latter half of the name - "Paso de la Tijera", means "Pass of the Scissors". This name was used by the early Spanish to describe the pass through the nearby hills, which resembled an open pair of scissors. Since the area was known to people by two different names, the Ranch of the Marshes or Pass of the Scissors retained both designations. To simplify the text, it will be referred to as "La Tijera".

For many years following the first Spanish settlements in California these particular hills and marshy fields were left unclaimed and considered to be part of the public lands belonging to the citizens of the pueblo of Los Angeles. Since the area was not formally granted until 1843, it seems likely that squatters from the pueblo built the La Tijera adobe for the purpose of raising cattle on the surrounding land. It was common for townspeople at Los Angeles to take advantage of the wide-open public lands to graze their livestock at no cost.

Rancho La Tijera was determined to be 4,481.05 acres. In comparison to modern streets, the boundary lines are described as follows:

A line following the same route as Exposition Boulevard between La Cienega Boulevard and 3rd Avenue formed the north boundary. From Exposition Boulevard and 3rd Avenue the line headed due south to Vernon Avenue. At Vernon, it jutted east a few blocks to Arlington Avenue and continued south along Arlington until it reached Slauson Avenue. The southern boundary commencing at Slauson and Arlington traversed westward to a point just west of La Brea Avenue. From here, a line angled in a northwesterly direction to Stocker Avenue in Baldwin Hills. A westerly line roughly paralleled Stocker to a site just west of La Cienega Boulevard. From here, the western boundary started northward and followed the course of La Cienega back to Exposition Boulevard.

Vicente Sanchez

Don Vicente Sanchez is first mentioned in early records as living in the Los Angeles pueblo in 1814. He married a woman named Maria Victoria Higuera. It seems that he was difficult individual to deal with. He was described as being a vicious, gambling and quarrelsome fellow, though of some intelligence and wealth. Sanchez had an embattled career in local politics. In January 1822, he was arrested by Comisionado Antonio Carrillo and sent to Santa Barbara in irons. The reason for his imprisonment was not specified, but the cause was most likely due to some sort of political disagreement. In 1826, he was a member of the electorate and may have assumed the vacant position of the alcalde of Los Angeles the following year.Sanchez was alcalde of the pueblo from 1830 to 1831. The population of Los Angeles in 1830 was 764. His term was plagued with problems. First, his election was deemed invalid, because at the time he was also serving as a member of the Assembly of the province. In April 1831, he was ousted from office and replaced by Juan Alvarado, the first regidor (lead councilman)of the town council. Governor Manuel Victoria intervened on his behalf and reinstated Sanchez to alcalde. In the latter part of that year, there was talk in the pueblo of plotting a revolt against Governor Victoria. Alcalde Sanchez, a staunch supporter and protege of the governor, had fifty of Los Angeles' leading citizens imprisoned, and he exiled Jose Antonio Carrillo, Pio Pico and Abel Stearns to Baja California.

The three expelled men reached San Diego where they were joined by Juan Bandini. They raised a force of 150 men to be led by Carrillo. The rebels marched to Los Angeles and released all political prisoners. In turn, they placed Vicente Sanchez in jail and called for Victoria to step down from office. Victoria headed south from Monterey to halt the rebellion. The two sides met on the field of battle near the Cahuenga Pass on December 5, 1831. A minor skirmish developed and resulted in both sides each suffering a single fatality. Victoria was himself injured, but was declared the victor of the military engagement because Carrillo's forces left the battlefield. However, Victoria decided to abdicate his governorship and return to Mexico. Jose Maria Echeandia took his place.

When Sanchez was released from jail, he went north to raise an army in order to restore a legitimate form of government in Los Angeles. He was able to recruit about twenty convicts, most of which were imprisoned in the past for rebellious actions. While heading south, the rowdy group abandoned Sanchez after they questioned his credibility. Sanchez had promised them complete exoneration if they helped him retake Los Angeles. But, they learned that Sanchez intended to use them as his own private security force instead of public service role which they were led to believe.

On May 23, 1835, the pueblo of Los Angeles was made the capitol of California by a national decree from Mexico. Sanchez offered for lease some of his own property to be used to house government offices. In 1836, he served in the diputacion, otherwise known as the assembly or an advisory committee to the governor. The following year, he took part in a revolt led by Manuel Requena against Governor Juan B. Alvarado. Sanchez was appointed to the position of sindico of Los Angeles. As sindico, it was his duty to receive or take charge of property under litigation and liquidated assets of those who were bankrupt.

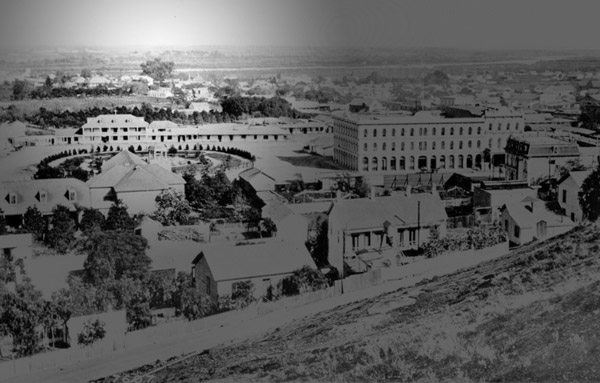

In 1841, Manuel Micheltorena arrived from Mexico to assume the governorship of Alta California. On December 31, 1841, Governor Micheltorena was sworn in during a ceremony at Don Vicente's magnificent adobe near the plaza. A grand ball honoring the governor was held thereafter. The Sanchez adobe was one of the finest homes in Los Angeles at the time. Being long and spacious it was similar in size and appearance to Abel Stearn's mansion "El Palacio" (the Palace). The two-story adobe was located just south of the plaza on a small thoroughfare, which became Sanchez Street in 1861. The house was razed and replaced with a building known as Sanchez Hall. The public meeting hall was replaced in the 1870s by the historic Garnier Building, which still exists on the site. The area became the core of the original Chinatown. It is now part of El Pueblo State Historic Park.

Sanchez was appointed as Comisionado de Zanjas (Commissioner of the Ditches) in 1844. With this appointment he was placed in charge of the maintenance and fair distribution of the pueblo's irrigation system. In 1845, he was elected alcalde for the second time. Like his first term as mayor, it was a controversial affair. Sanchez made unpopular decisions and often created discord among the townspeople. Minor rebellions surfaced occasionally, but none as poignant as in 1831. With all the citizen complaints about Sanchez, he was still respected as a strong leader.

When Don Vicente received the grant of Rancho La Tijera in 1843, he was unable to devote much time to ranching because he was occupied with his civic responsibilities at the pueblo. He must have had a mayordomo or a relative in charge of ranch operations. The mayordomo may have found the old adobes at the base of the hills a suitable home and headquarters for La Tijera. It is possible that Sanchez built one of the adobes or may have expanded and improved them to make the place habitable. The abundant wetlands and grassy hillsides on the rancho provided adequate nourishment to the Sanchez cattle.

Rancho La Tijera was bounded to the north and west by two other ranchos; Las Cienegas and Rincon de los Bueyes, respectively. Like Vicente Sanchez the politician, Vicente Sanchez the neighbor was an equally contemptible character. He was constantly disputing boundary lines of the adjoining ranchos. To the west the dividing line between La Tijera and Rincon de los Bueyes was a deep ravine where today's La Cienega Boulevard cuts through the Baldwin Hills. Sanchez claimed the entire ravine and additional land not belonging to him. When the hogs of Francisco Higuera, owner of an adjacent rancho, strayed on to La Tijera, Sanchez publicly accused the other rancher of stealing his land. The fight between the two became so heated that Governor Pio Pico had to step in to control the situation. Knowing well of the wrath of Sanchez, Pico settled the matter in favor of Higuera. As for Rancho Las Cienegas, Don Vicente claimed that the whole property belonged to him, although it was granted to Francisco Avila. Sanchez lost this claim as well.

Tomas Sanchez

Vicente Sanchez died in 1850 and left his Rancho La Tijera and the town house to his son, Tomas, and his two daughters; Dolores and Maria. Don Vicente's daughters chose to live at the adobe in town and left the ranching to their brother. Tomas A. Sanchez was possibly born in 1802. Like his father, Tomas was involved in civil service. In 1843 he was listed as being the tax collector of Los Angeles. In 1846, he served in the Californio (Spanish Californians) forces led by General Andres Pico during the Mexican-American War. He took part in the Battle of San Pasqual, which was fought twenty-eight miles northeast of San Diego on December 6, 1846.After the American conquest of California, Tomas Sanchez remained active in politics under the new government. In the 1850's he was a member of the Democratic Party. In the following decade, Sanchez remained a loyal Democrat and a staunch supporter of James Buchannan for President of the United States. At the time, most of Los Angeles was Democratic and strongly favored Confederate causes and the secessionist movement.

In the early 1850s, Los Angeles was a dangerous place to live. Averaging about one murder per day, it had one of the worst murder rates in the country for a modest sized town. In a two-year span (1851-52) there were forty-four murders on one small side street alone. Tomas Sanchez often participated in vigilante groups scouring the countryside for violent criminals. In July 1856, racial tension was high in Los Angeles between Mexican-Americans and Anglo-Americans due to a shooting death of a Mexican by an Anglo Sheriff. The shooting resulted during a struggle when the lawman attempted to evict the other from his home. Bands of Mexicans planned for a rebellion. The rebels were responsible for shooting and wounding a sheriff. Sanchez, along with other prominent Mexican-American citizens helped to put a halt to the revolt. Later that year, Tomas Sanchez, along with Andres Pico helped to create a volunteer group of vigilantes known as the City Guards. It was the first organized police force in Los Angeles.

One of Sanchez's most famous pursuits was that of the bandidos led by the notorious Juan Flores and Pancho Daniel. Flores and Daniel escaped from San Quentin Prison in 1856. They fled south toward Los Angeles and along the way they accumulated a band of fifty outlaws. The desperados took over the San Juan Capistrano Mission as their headquarters and began terrorizing Southern California with brazen acts of robbery and murder. The legendary Flores-Daniel gang was considered revolutionaries by many because they targeted mainly Anglo victims, but in reality, they victimized their own race as well. Early in 1857, Los Angeles Sheriff, James Barton led a posse of six deputies in pursuit of the murderers. Barton tracked the band of outlaws into the hills near the Orange County rancho of San Joaquin. Barton and his posse were ambushed and killed by twenty members of the gang.

Outrage was the emotion felt in Los Angeles when news of the ambush reach there. Federal soldiers from Fort Tejon, and a group of Texas Rangers from El Monte went in search of the killers. Also joining the hunt were a company of sixty mounted Californio's lead by Andres Pico and Tomas Sanchez. Sanchez and Pico supplied their own horses for the posse. The Californio company was the first to find members of the Flores-Daniel at Canada de Santiago (Santiago Canyon). Volleys gunfire erupted, echoing throughout the canyon walls and the outnumbered bandit fled deeper into the Santa Ana Mountains.

During their flight they became separated and eventually killed or captured by the other posses. Flores was one of the last to be captured. He headed through Trabuco Pass and was captured by the Rangers near Flores Peak, named for the celebrated bandit. Flores escaped his captors for a brief period, but the exhausted and wounded bandit was recaptured at Santa Susanna Pass, northwest of the San Fernando Valley. Astonishingly, with all the search parties in the area, Pancho Daniel managed to escape. In February, 1857, in front of 3,000 spectators, Juan Flores was hung for his crimes at Fort Moore Hill in Los Angeles. Pancho Daniel was arrested a year later near San Jose, California. He met the same fate as his cohort, Flores.

For his prior experiences in law enforcement and especially his role in the seizure of the Flores-Daniel band, Tomas Sanchez was elected the Sheriff of Los Angeles County in 1860. Serving as sheriff from 1860 to 1867, Sanchez was the primary law enforcement agent in a lawless land. In addition to his duties of tracking down criminals, he had to seek out and return Union army deserters from Camp Drum in Wilmington. He was also in charge of seizing properties in the county from owners who were delinquent in paying their creditors and held public auctions to sell those properties.

As jailer of the county, he had to transport convicted criminals to prison. This was often a risky task for a lawman. One such occasion came to a violent conclusion. In 1863, crime in Los Angeles was at one of its peaks. In the same year, a rancher named John Rains was murdered near Azusa. The killer, Jose Cerradel was arrested and convicted of murder. Cerradel received a ten-year sentence for his crime. Angry citizens thought the punishment was too lenient. Sheriff Sanchez took the prisoner to Wilmington where they boarded the steamer Crickett en route to San Quentin Prison. A mob of vigilantes boarded the vessel and forcibly took Cerradel from the custody of Sanchez. The mob hung the convicted man from the mast. They took down the dead man, weighted him down with rocks and dumped him into San Pedro Bay. Vigilante violence and lynchings were common occurrences in the county at the time.

As a rancher, Sanchez didn't take much interest in Rancho La Tijera. However, he conducted various agricultural endeavors in the south and western sections of the rancho. Sanchez preferred to live on the property belonging to his wife, Maria Sepulveda Sanchez. She was a member of the Verdugo family who owned Rancho San Rafael. She inherited over 900 acres of San Rafael from her mother, Rafaela Verdugo Sepulveda. In the 1870s, Tomas and Maria Sanchez built an adobe home on the property. It still stands at 1330 Dorothy Drive in the city of Glendale. Sanchez gradually began to sell off portions of La Tijera. In 1874 he sold 360 acres to a blacksmith named Andrew Joughins for $6,000.

It wasn't until 1887 that Tomas Sanchez received the official United States Patent for Rancho La Tijera. By then, it was no longer in his possession. Tomas Sanchez sold Rancho La Tijera for $75,000 in 1875. The buyers were four men; Francis Pliney Fisk (F.P.F) Temple, Arthur J. Hutchinson, Henry Ledyard and Daniel Freeman. Temple was half owner of Rancho La Merced and President-owner of the Temple and Workman Bank in Los Angeles. Henry Ledyard was an executive with the Temple and Workman Bank. Daniel Freeman was owner of Rancho Aguaje de la Centinela, which was a mile south of Rancho La Tijera. Freeman founded the nearby City of Inglewood.

The rancho was divided into four quarters with each of the four men getting a share. However, their ownership did not last very long. In 1875, F.P.F Temple experienced heavy financial difficulties with his bank. He appealed to San Francisco millionaire, Elias J. (Lucky) Baldwin for help. Temple borrowed over $300,000 from Baldwin to bail out his failing bank. Temple put up all his land holdings as collateral. In January 1876, the Temple and Workman Bank defaulted on the loan and was closed. Temple lost everything he owned as result. Baldwin foreclosed on the mortgages of Temple's properties.

Temple's interest in La Tijera was not an official part of the loan agreement, but Lucky Baldwin refused to grant the loan unless Temple sold his and Ledyard's share of Rancho La Tijera to the millionaire. When the four owners acquired the rancho, they signed an agreement stating that each man, when deciding to sell their share, must first offer his respective interest to one of the other three owners at the same price offered by an outsider. Arthur Hutchinson offered Temple the same amount that Baldwin was asking for the land, but Temple refused. Temple was desperate and disregarded the agreement with his fellow co-owners. Temple and Ledyard deeded their shares to Baldwin on December 2, 1875. The price Baldwin paid for this undivided half interest in Rancho La Tijera was $35,000. Temple died a broken man five years later.

In time, Hutchinson bought out Daniel Freeman's quarter interest and Andrew Joughin's 360 acres. Hutchinson sold the remaining half interest to Elias J. Baldwin for $60,000 in 1886. Rancho La Tijera was whole once again. Baldwin gave his name to the hills that dominated the western section of the rancho and thereafter became known as the Baldwin Hills. He used the ranch primarily as a sheep pasture, but it was not profitable. In the late 1880s, Baldwin's cousin, Charles Baldwin and his wife Julia, took over the ranching operations on La Tijera and converted it into a successful dairy. The dairy earned a respectable $25,000 a year.

"Lucky Baldwin"

Elias Jackson Baldwin was born on April 3, 1828, in Hamilton County, Ohio. In 1834, his family moved near South Bend, Indiana where he grew up on a farm. In 1853, Baldwin came to California by wagon train and made a handsome profit along the way. When Baldwin arrived in San Francisco he made enough money to buy a hotel. He started other business ventures and invested in real estate. In the 1860s, he began investing in a number of Comstock silver mines in the Sierra Nevadas. By the end of 1874, he amassed over $5,000,000. By this time Baldwin received the nickname "Lucky" because he was successful in every business he attempted and everything he touched seemed to turn to gold.In 1875, Baldwin began buying real estate in Southern California and by 1880, he acquired over 35,000 acres of Southland property. In addition to La Tijera, his land holdings included; Rancho Santa Anita, Rancho San Francisco, Rancho La Merced, Rancho Potrero Grande, Rancho Potrero Chico, Rancho Potrero Felipe Lugo, Rancho Potrero Mission Vieja de San Gabriel, half of Rancho La Puente and numerous lots in Los Angeles. Combined with his properties in San Francisco, Lucky Baldwin was one of the wealthiest landowners in the state.

The flamboyant Baldwin chose Rancho Santa Anita as him home base, living in the old Hugo Reid adobe. Here he bred and raced fine thoroughbred horses. In 1882, he built the Queen Ann Cottage on his 8,000 acre Santa Anita. This ornate Victorian mansion still stands and is a part of the 127-acre Los Angeles County Arboretum.

In the 1880s, Baldwin began subdividing his ranchos through his Los Angeles Investment Company. He had a special place in his heart for Rancho La Tijera and refused to part with. In 1908, the 3,500-acre rancho was estimated to be worth $7,000,000. With the Redondo Electric Railway and the Southern Pacific Railroad crossing the rancho, the demand for city lots and residential tracts increased. The price per acre was steadily rising. But, Baldwin had no desire to sell the land, which just sat idly not producing much income.

Baldwin died in 1909. His estate listed Rancho La Tijera as his most valuable possession. Baldwin's daughter, Clara Baldwin Stocker, was one of the heirs to the Baldwin fortune, which included Rancho La Tijera. Stocker Avenue coursing through Baldwin Hills was named for her. Shortly after Baldwin's death, his heirs were willing to sell La Tijera for only $2,225,000. Baldwin's executor, Hirum Unruh, protested the premature decision to sell by making the claim that the land would be worth $5,000,000 more within the next five years.

The Baldwin heirs sold large parts of the rancho and the Los Angeles Investment Company began subdivision of the acreage. Angeles Mesa was laid out and was renown throughout the nation as a premier neighborhood. Development and growth of the community was rapid. The tract was annexed to the city of Los Angeles in two stages; first on July 27, 1922, and the remainder on October 5, 1922.

In 1917, oil men began drilling wells in Baldwin Hills. Several gushers of black gold erupted and the Inglewood Oil Field was born. From 1917 to 1960, fossil fuel was continuously pumped out of Inglewood Oil Field, which caused the Baldwin Hills to sink at least ten feet. This phenomenon is a geological condition known as subsidence. The subsidence was a significant factor in causing the failure of the Baldwin Hills Reservoir on December 14, 1963. The flood resulting from the reservoir collapse caused extensive damage and a few deaths when torrents of water came through residential areas below.

In 1932, Baldwin Hills gained notoriety when it housed world class athletes during the 1932 Olympiad held in Los Angeles. Angeles Mesa and the Crenshaw Districts was the site of the Olympic Village. Over 600, double room, houses were built in the hills west of Crenshaw Boulevard south of Vernon Avenue.

During the 1920s, the La Tijera adobe underwent several renovations. It became the clubhouse of Sunset Fields Golf Course. The Sunset Golf Association leased the estate around the adobe from the Baldwin heirs. After World War II, the area was subdivided, becoming a residential neighborhood replacing the greens and fairways of the public golf course. Later, the adobe was converted into a Women's Club.

In 1948, the May Company Department Store was completed below the hill east of the adobe. The following year the Broadway Crenshaw Shopping Center was built next to the May Company. The former rural environment about the ancient adobe was finally eliminated. From the long front corredor (porch) of the La Tijera adobe the nineteenth century ranchero would be able to see empty fields all the way to the tiny pueblo. Today, from the same vantage point, one can see a busy shopping complex and mammoth sky scrapers that tower over the former site of a sleepy little cow town of adobe structures known as Los Angeles.

On February 16, 1984, the Native Daughters of the Golden West Parlor #247 placed a small rectangular plaque on the exterior wall of the adobe next to what was probably the front door. On March 26, 1990, the adobe was declared Los Angeles Historical Cultural Landmark 487.

Today, the Rancho Las Cienegas O' Paso de la Tijera adobe stands on a one acre, asphalt parking lot. The building is currently being used by a real estate company as private offices. It is difficult to get a sense of how the original structure appeared. The north and south wings may have been additions or annexations of separate structures. The long central section appears to be the oldest. The east side of this section was the front of the house and faces the large parking lot. On the opposite side, the courtyard faced the hill. Slender wood posts support the overhanging roof to the front, while numerous doors and large widows are spaced all around the building. Along the south wing, some windows and doorways are apparently sealed by cement and plaster. The outside walls are a coffee color, which contrasts well with the dark brown trim. The eaves of the roof are wood, but the peaked roof is covered with deteriorating, matted, processed shingles which does not fit the style of the rest of the adobe building. This replaced a previous shake roof. A high cinder block encloses the west side of the house, partially obstructing the view of the house from the street.

Today, the Rancho Las Cienegas O' Paso de la Tijera adobe stands on a one acre, asphalt parking lot. The building is currently being used by a real estate company as private offices. It is difficult to get a sense of how the original structure appeared. The north and south wings may have been additions or annexations of separate structures. The long central section appears to be the oldest. The east side of this section was the front of the house and faces the large parking lot. On the opposite side, the courtyard faced the hill. Slender wood posts support the overhanging roof to the front, while numerous doors and large widows are spaced all around the building. Along the south wing, some windows and doorways are apparently sealed by cement and plaster. The outside walls are a coffee color, which contrasts well with the dark brown trim. The eaves of the roof are wood, but the peaked roof is covered with deteriorating, matted, processed shingles which does not fit the style of the rest of the adobe building. This replaced a previous shake roof. A high cinder block encloses the west side of the house, partially obstructing the view of the house from the street.This historic treasure is virtually hidden and its existence is known by a few. If this adobe was actually built in the late 1700s it would be the oldest structure in Los Angeles. As of this writing, there is no known effort to preserve the adobe.

Adobe de Rancho La Tijera

3725 Don Felipe Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90008